The idea of pettiness toward the Indiana Fever star isn’t about Clark, but rather about how we treat Black women we think are upset by her success

Caitlin Clark was always going to be the biggest story for at least the first few weeks of the 2024 WNBA season. She came into the league as the best player in college, having won National Player of the Year, and carried her Iowa team to the national championship game. She is also a major factor in the way that ratings and ticket sales are skyrocketing.

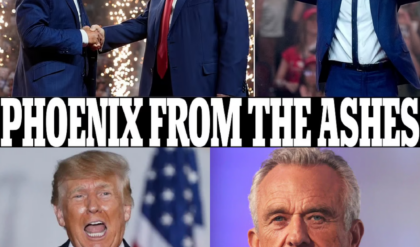

Six games into her rookie season with the Indiana Fever, however, the talk about Clark’s career has been less about her play and more about where she sits in the center of our own sociopolitical projections, with male athletes such as Charles Barkley and LeBron James even chiming in about the way she’s perceived, treated and embraced. Much of the consternation is about the notion that Clark is somehow being mistreated, but the question is who supposedly mistreats by and what it says about what we feel toward the rest of the players in the WNBA.

“You women out there, y’all petty, man,” Barkley said, his brow furrowed as he stared into the camera during the pregame show for Game 1 of the Western Conference finals last Wednesday. “Y’all should be thanking that girl [Clark] for getting y’all ass private charters. All the money and visibility she’s bringing to the WNBA, don’t be petty like dudes. Listen, what she’s accomplished, give her her flowers.”

Barkley’s comments came on the heels of LeBron’s own about Clark on his “Mind The Game” podcast with JJ Redick: “Don’t get it f—ed up. Caitlin Clark is the reason why a lot of great things is going to happen for the WNBA. But for her individually, I don’t think she should get involved on nothing that’s being said. Just go have fun.”

Both James and Barkley allude to negative comments, especially those coming from women in the WNBA toward Clark, but it’s unclear where exactly they think the pettiness is coming from. Who are the women hating on Clark?

Aliyah Boston (left) and Caitlin Clark (right) of the Indiana Fever talk to the media after the game against the Los Angeles Sparks on May 24 at Crypto.com Arena in Los Angeles.

Aliyah Boston (left) and Caitlin Clark (right) of the Indiana Fever talk to the media after the game against the Los Angeles Sparks on May 24 at Crypto.com Arena in Los Angeles.

ADAM PANTOZZI/NBAE VIA GETTY IMAGES

You can scour the WNBA discourse online for quotes and be hard-pressed to find comments critical of Clark or any that can be anywhere remotely close to being characterized as “pettiness” or “hating.” Over the past few days, social media has been repeating the same handful of comments that have been misconstrued as negative about Clark. It only takes a few extra seconds to evaluate what was actually said to see that the comments are harmless, and valid.

When Clark’s college rival Angel Reese and her Chicago Sky beat the New York Liberty over the weekend, Reese tweeted out, “And that’s on getting a win in a packed arena, not just cause of one player on our charter flight.” The since-deleted tweet was largely perceived as a slight at Clark, but it was in direct response to Barkley’s statement that it was Clark who’s responsible for the chartered flights.

Two other widely shared instances of supposed hate didn’t even come from WNBA players. One was a comment from The Atlantic columnist Jemele Hill to the L.A. Times: “We would all be very naive if we didn’t say race and her sexuality played a role in her popularity. While so many people are happy for Caitlin’s success — including the players; this has had such an enormous impact on the game — there is a part of it that is a little problematic because of what it says about the worth and the marketability of the players who are already there.”

Those comments led to a debate on “The View” in which co-host Sunny Hostin said. “I do think that she is more relatable to more people because she’s white, because she’s attractive.”

Both comments essentially say the same thing: race and sexuality play a role in Clark’s popularity. She’s an all-time great college player and a singularly popular star based on her own generational talent, but that’s also aided by her being a straight white woman. That’s how these things work in America. History has shown that if she were a non-white, non-straight superstar with the same talent, she would not be as popular or the megastar she is now. Both Hill and Hostin go out of their way to acknowledge Clark’s greatness, too. That doesn’t stop publications and people on social media from mischaracterizing their comments. Like this.

If anything, the majority of the commentary about Clark has not only supported her but it’s crept into the unfortunate space of coddling a resilient, tough-as-nails athlete who doesn’t need it. When Clark gets hit with a hard foul, it’s somehow an indictment on the league. When her teams struggle (they are 1-6 at the time of this writing), it’s supposed to be a reason for the league to panic, and even rethink its scheduling. This is all despite the fact that hard fouls and early-season losses happen all the time to rookies across all sports – it just happened to Reese on May 25 after Alyssa Thomas delivered a flagrant 2 blow during the game. Yet it’s somehow a uniquely cruel thing when it happens to Clark.

Which brings me back to Barkley’s and James’ comments. They didn’t pinpoint exactly who the haters are because they don’t seem to exist. We’re seeing more fabricated slights at Clark — like anger over Chicago Sky player Brianna Turner’s tweet about pasta being misconstrued as a diss to Clark – than actual direct comments from any WNBA player.

Instead, what we’re dealing with is an age-old stereotype where race and gender are front and center. Because the idea of pettiness toward Clark isn’t about Clark herself, but just about how we treat the women we allege are upset by her success — namely Black women.

Caitlin Clark (right) and Angel Reese (left) at the WNBA draft held at the Brooklyn Academy of Music on April 15 in New York City.

Caitlin Clark (right) and Angel Reese (left) at the WNBA draft held at the Brooklyn Academy of Music on April 15 in New York City.

CORA VELTMAN/SPORTICO VIA GETTY IMAGES

One of the prevailing stereotypes about Black women is that they have an inherent jealousy of white women, especially white women they’re supposed to be in competition with. When Black women wear certain hairstyles, they’re told they’re trying to look like white women — Chris Rock made a whole movie perpetuating this notion. When Black men date or marry white women, they sometimes project the idea that Black women are jealous and upset by the interracial relationship — Taye Diggs and Alfonso Ribeiro, among others, have maintained this stance without offering so much as an anecdotal example. And there’s a prevalent belief that the WNBA, which is 70% Black, is full of women who are jealous and threatened by Clark’s superstardom in spite of the fact there isn’t any tangible example to back it up.

Because if these women were prone to being threatened by any rookie megastar that enters the league, we’d be accusing them of being jealous and petty toward Reese. While she’s not as popular or famous as Clark, Reese is still a superstar who’s garnered mainstream attention, rubbing elbows with celebrities and elevating the star power in the WNBA. Yet there’s no discussion about pettiness or jealousy toward her. Just Clark. And that’s not by mistake.

On May 25, Las Vegas Aces coach Becky Hammon outlined the racial politics in play. “It’s construed as some of our minority Black and brown women are hating on her because she’s white and that is not the case,” she said after the Aces’ 99-80 win against Clark’s Fever. The “hatred” toward Clark only exists in the minds of people who have their own beliefs about how Black women feel about white women, even in the absence of any evidence to back up said beliefs.

But it’s not just the other women in the WNBA who are suffering from how we coddle Clark. It’s Clark herself who suffers.

Clark, for her part, has done everything right so far. She’s taken her lumps and losses in stride. She’s fought through rough games, excessive turnovers and stout defense to only get better. There’s already a stark difference from the player who was struggling to get by the defense in her first game and the player who hit the dagger shot from the logo to secure the Fever’s first win on May 24. The Fever have back-to-back No. 1 picks in Clark and Aliyah Boston, and most likely another high pick in next year’s draft. The team will be good. Clark will get better. She still has a great chance to be Rookie of the Year and her ceiling is still a multi-time MVP and WNBA champion. Greatness is right around the corner.

Unfortunately, she’s having to sit at the center of a sociological firestorm. She hasn’t complained or asked for preferential treatment, but when it’s thrust on her it only places more of a microscope on every mistake and loss. When trolls attack Boston for the Fever’s record, causing her to leave social media, or spend years attacking Reese for daring to taunt Clark a year ago, it’s an unfair byproduct of fanatical defenses of Clark. When Reese gets blasted with a flagrant 2 foul, the same people up in arms over how Clark is getting treated on the court don’t find it in their hearts to get outraged over a superstar rookie potentially getting hurt by an aggressive player. When media personalities or fanatics act like Clark is under some unfair duress because she’s losing, it looks like she’s being babied.

Again, Clark isn’t asking for any of that. She’s just trying to play basketball and be her best self. All of the other stuff takes away from her goal. If you want someone to start getting actual haters and disdain, then treating them like an untouchable savior who should be exalted every time she graces the league with her presence is a surefire place to start.

But let’s imagine that Clark was actually getting targeted. Why would that even be a bad thing? Any time a player has entered any league as the supposed chosen star, they’ve had to prove themselves to be just that. It’s how competition works. ESPN’s Elle Duncan laid out how the pearl-clutching over anyone wanting to unceremoniously welcome Clark to the league reveals a double standard about how women are perceived in sports.

“It is embarrassing, because if this was the men and you just watched a bunch of other dudes fawn over someone all the time … if that was men, you’d call them weak. That would be a soft move,” Duncan said.

Clark is going to continue being a game-changer for the WNBA. She’s going to be something beautiful for a league that is full of players, past and present, who have paved the way for her to make the splash she’s already made. All we as fans have to do is enjoy it without reducing all parties involved to unsubstantiated characterizations.

Clark doesn’t need our protection; and she especially doesn’t need it from a group of nonexistent aggressors who are based on stereotypes and regressive politics. She and every single woman involved in the WNBA have and always will deserve better.