RICHARD MILNER

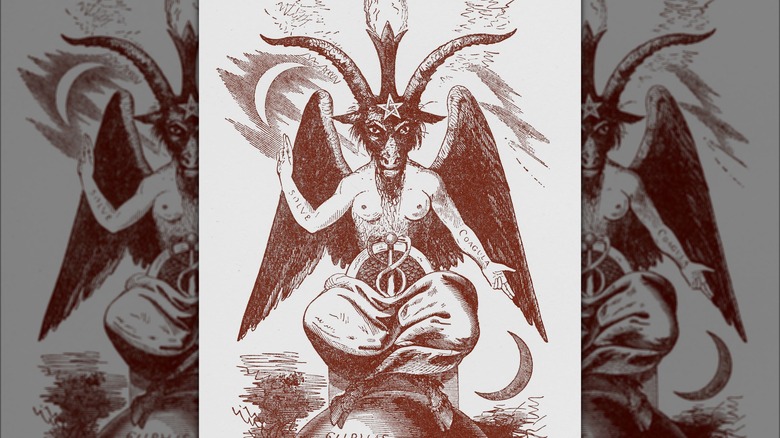

Murmur the name “Baphomet” in certain religiously inclined circles and you’ll doubtlessly see some hackles rise. “You mean Beelzebub?” the question might go. Or Asmodeus, Samael, Molech, Abaddon, Ba’al, something-something demon devil Satan Lucifer, etc. To some, particularly Christians, Baphomet is an ancient malevolent figure representative of a profound and vague evil also associated with modern-day Satanists. Baphomet’s even got a famous image that just might rank amongst the most widely-known occult portraits on Earth: a horned, winged, goat-headed, cloven-footed, bare-chested, and breasted figure sitting cross-legged with a snake-encircled caduceus in its lap. Spooky.

But, well … here’s the thing. Baphomet isn’t a real deity worshipped by anyone, and probably never was. The name first popped up during the crusades, when one Anselm of Ribemont in 1098 C.E. described Turks calling upon “Baphomet” during the Battle of Antioch. Whether or not Anselm spoke the Turk’s language is another issue entirely.

After that, “Baphomet” became a byword for “Muslim” associated with the prophet Mohammed. It also got tossed around to politically persecute everyone from the 14th-century Knights Templar to 19th-century Freemasons, who were both accused of Baphomet worship, e.g., non-Christian practices. The popular, horned image of Baphomet is a drawing from 19th-century French occultist and Kabbalistic author Eliphas Levi, who in 1854 wanted to sketch a figure that represented the union of opposites, notably male and female. Ultimately, the most disturbing thing about the character of Baphomet is how it’s been borrowed again and again, wrongfully used by those in power, and misunderstood by the public.

AN ARTIFACT OF THE CRUSADES

The word “Baphomet” doesn’t show up in history until 900 years ago via an unlikely source: the First Crusade from 1096 to 1102 C.E. Back in 1095 C.E. Pope Urban II called upon all Christians to march on Jerusalem and wrest it from Muslim control. By that point Jerusalem had been under Muslim rule for about 460 years, since Calipha Umar, one of Mohammed’s companions, conquered it in either 635 or 638 C.E. Dubbed the “People’s Crusade” for the peasants that marched alongside the crusade knights, the First Crusade proved successful when Christian forces won back Jerusalem in 1098. And, it’s the Siege of Antioch – and subsequent battle — that proved the most decisive encounter of the conflict.

It’s crusader Anselme of Ribemont who first mentions the word “Baphomet” — or Baphometh by the Latin spelling. Anselme was present at the Battle of Antioch, and wrote of the Turks inside the city, “As the next day dawned they called loudly upon Baphometh while we prayed silently in our hearts to God,” per 2010’s “Letters from the East: Crusaders, Pilgrims and Settlers in the 12th-13th Centuries.” Some think that “Baphometh” is a corrupted pronunciation of “Muhammed” or “Mahomet,” the latter being a Latinized spelling of the name. Medieval Christian writers even called mosques “Bafumarias.” Leading up to the 14th-century Renaissance, Baphomet crops up here and there in various texts when referring to Islam. From there, the term — and its associated fictional entity — evolved over centuries.

TEMPLARS AND THE HEAD OF JESUS

In the early 1300s, the figure of Baphomet took on a heretical, insidious meaning following the persecution of the Knights Templar. Originally named the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and the Temple of Solomon, the Templars appeared during the Crusades in 1118 C.E. as an armed organization devoted to helping Christian pilgrims safely make the journey to Jerusalem. In less than 20 years they’d received the pope’s blessing, exemption from taxes, and were allowed to build their own chapels. They gained tremendous power by the end of the 13th century, flourished across Europe, and established their own banking system whereby they allowed withdrawals based on goods that they safeguarded.

Come 1307 the French King Philip IV needed some money. In a single day, he arrested every Templar in France and handed them over to church inquisitors. The public had been whispering about secret devilry, cultish groups in the night, orgies, the desecration of sacred objects, etc., for decades before then. Tortured Templars started admitting to all these deeds, and other blasphemies like spitting on images of the cross or just being gay. The apex of torture-induced confessions involved an idol shaped like a head that the Templars called “Baphomet.” Some accounts said it was just a cat skull. One of the more snowballed, whackadoodle notions is that “Baphomet” was the actual, preserved head of Jesus. This is how Baphomet morphed from a vaguely scary idea into an anti-Christian entity representative of whatever evils its wielder imagined.

SKETCHED BY LEVI, NAMED BY LAVEY

We owe our modern portrait of Baphomet almost exclusively to 19th-century occultist and writer Alphonse Louis Constant, aka, Eliphas Levi. Levi was highly knowledgeable about esoteric practices, particularly Kabbalah, i.e., Jewish mysticism, and compiled much of what he knew into his landmark book, “Dogme et rituel de la haute magie,” published between 1854 and 1856. This book was translated into English in 1896 as “Transcendental Magic: Its Doctrine and Ritual.”

Levi’s original French book cover portrayed the well-known, goat-headed, bare-chested, cross-legged figure that’s come to be called “Baphomet.” As the University of Amsterdam explains, Levi intended his drawing to be a “symbolization of the equilibrium of opposites,” one that had nothing to do with Baphomet, Satan, the Knights Templar, the Crusades, etc. He dubbed his figure the “Androgynous Goat of Mendes,” or “sabbatical goat,” and took visual inspiration from the 1608 witch-hunting bestiary, “Compendium Maleficarum,” which contains a similarly goat-headed, winged creature. Levi did comment on the name “Baphomet” at one point, saying that it was a reverse-spelled Latin acronym for “the father of the temple of universal peace among men.”

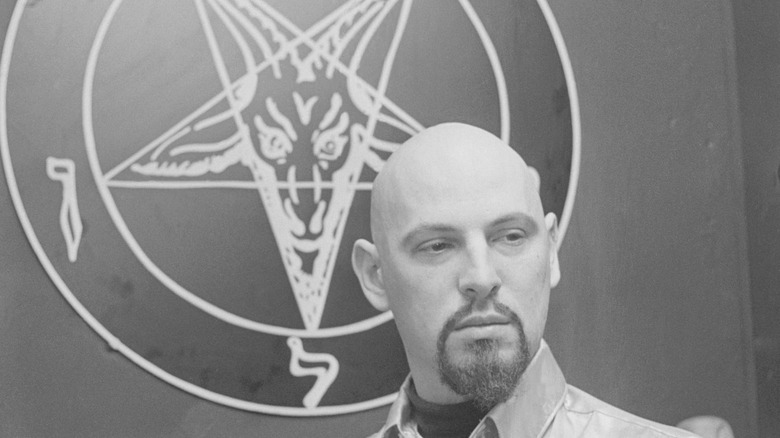

None of this is particularly disturbing, at least until we run into Anton LaVey. LaVey is the founder of the Church of Satan and author of 1969’s “Satanic Bible,” a book that all but single-handedly generated every modern stereotype about pentagram-doodling devil worshippers sacrificing animals in basements. LaVey took Levi’s drawing and adopted it as the official symbol of the Church of Satan in 1966.

ALEISTER CROWLEY TIED BAPHOMET TO THE OCCULT

Before jumping to the present, we’ve got to mention occultist Aleister Crowley, who depending on who you talk to is either one of the most preeminent ritual magicians of recent ages or a kook with a boundless ego — possibly both. Crowley preceded Church of Satan founder Anton LaVey in solidifying the character of Baphomet as inherently “Satanic” even though he had nothing to do with Satanism whatsoever.

Dubbed the “wickedest man in the world” by the media of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Crowley was one of the most notorious and colorful figures of his time. Essentially, Crowley borrowed a host of elements from different belief systems — heathen rituals, Buddhism, sex magic, Kabbalah, Eliphas Levi’s sabbatical goat, rites of secret societies like the Freemasons, etc. — and scrambled them all into his own magical system: Thelema. Crowley defined Baphomet as the “divine androgyne,” a symbol of cosmic balance. He also redefined the biblical figure of Lucifer as a kind of edgy rebel and named himself — Crowley — “the Great Beast 666.” He also took a shine to Levi’s sabbatical goat picture.

So what does this all mean? Crowley inadvertently fused the occult with Satanism, and Satanism with Baphomet. From the outside looking in, it was a simple connection to make, without any complexities to consider. Once again, “Baphomet” became a byword for whatever someone wanted to believe.

THE CHURCH OF SATAN AND THE SATANIC TEMPLE

We mentioned that Anton LaVey took Eliphas Levi’s goat-person drawing and made it the symbol for the Church of Satan. But to be specific — and to complicate things even more (if that’s possible) — LaVey used a modified version of Levi’s drawing. In 1897, French poet Stanislas de Gauaita took the goat head from Levi’s figure, drew an upside down pentagram around it, and voila: instant iconic symbol for LaVey and others to use. So, after many steps, many iterations, and many people poaching ideas from others, we arrive at the present.

Nowadays, the image of “Baphomet” — quotes intentional — has all but solidified in popular culture as synonymous with devilry and evil. Those who don’t know its history assume it’s an actual entity from ancient times to be taken literally, like a statue of Zeus that means Zeus and has always meant Zeus. The Satanic Temple — a non-theistic organization unrelated to the Church of Satan — even erected statues of Baphomet to make a point about religious freedom in the United States. Suffice it to say, many folks in places like Little Rock, Oklahoma City, and Detroit weren’t too happy about it. But good news: The Satanic Temple sells Baphomet statues if you want to plunk one on a shelf at home. For them and everyone else, Baphomet remains an idea or a symbol. Although, depending on your perspective, maybe that’s all that a god is.