‘Bog standard’ act ends Swan’s Brownlow dream as Crow stays sidelined for a month

Sydney superstar Isaac Heeney is ineligible for the Brownlow Medal after failing his AFL Tribunal appeal of a one-game striking ban, while the four-game ban for Adelaide’s Izak Rankine was also upheld.

Heeney will miss Saturday’s clash with North Melbourne but perhaps more importantly cannot win the AFL’s top honour.

He is likely to lead the count in the early stages before the likes of Collingwood’s Nick Daicos, Carlton’s Patrick Cripps and the Bulldogs’ Marcus Bontempelli catch up.

Watch every game of every round this Toyota AFL Premiership Season LIVE with no ad-breaks during play on Kayo. New to Kayo? Start your free trial today >

WHAT’S GAMBLING REALLY COSTING YOU? Set a deposit limit.

Heeney argued his strike was careless or not even reportable, rather than intentional, after swinging his arm back and leaving St Kilda’s Jimmy Webster with a bloody nose.

Vision from Fox Footy’s The First Crack was shown during the hearing, as it was the best available vision of the incident.

The medical assessment showed Webster had a blood nose but required no further treatment.

Heeney explained he was “trying to get separation and palm off” before realising teammate Justin McInerney was not yet ready to kick.

He recalled being held on his right shoulder blade and left side by Webster before “forward craft … to try and swat his hands away” in “an angle where his hand would be on my back, in a downward motion”.

“He had a hold of me … I’m just trying to swat his hands away, I don’t want to be held,” Heeney said, explaining he didn’t expect Webster to be so low.

“He’s taller than me and just where his hand on my back was is where I was swatting.”

Having “accidentally” made contact Heeney “took full focus off the game” and his “thoughts went straight to (Webster)”.

“I wanted to swat his hands away, I didn’t want to hit him anywhere other than the hands,” Heeney said.

“With your forward craft this happens a lot during a game … probably 50 to 100 times in some games.”

Andrew Woods for the AFL argued Heeney looked at Webster as he swung backwards, which the Swan disagreed with.

“The position of his head was clear to you at least in your peripheral vision,” Woods said.

“I don’t recall seeing his head in my peripheral vision,” Heeney replied.

Woods also disputed that Heeney was swinging downward – which the vision seemed to disagree with, but Heeney said his arm “came up to come back and down … it clipped his hand which raised it up a bit there”.

Heeney accepted that the outside of his hand made contact with Webster’s face.

Woods for the AFL argued Heeney was clearly intending to make contact, regardless of where he actually made contact, pointing to the new rule where a player is “forcefully trying to push or fend off a player to gain separation”.

“He either saw the head was there or should’ve known the head was there,” Woods said.

Duncan Miller for the Swans argued the action was in play given they were about to contest the ball and pointed to the word “usually”, not “definitely”, being used in the new rule.

“50 metres from the ball though, isn’t he?” Tribunal chair Jeff Gleeson asked.

.@DavidZita1 provides an update on the early stages of the Isaac Heeney tribunal case.

📺 Watch #AFL360 on Ch. 504 or stream via @kayosports: https://t.co/7kvglvpWSC pic.twitter.com/VnwO4yTNyq

— Fox Footy (@FOXFOOTY) July 9, 2024

The Swans also pointed to Heeney’s immediate reaction of stopping and “tuning out of the game” as clear evidence of his intention not being to strike.

“It cannot be that the inevitable consequence of an act of that kind (holding) … is a forward doing their forward craft of trying to swat that hand away, is an outcome that is consistent with intentional (striking),” Miller said.

“It would not be expected … that someone in Heeney’s position would expect he’s going to find someone who’s a couple of inches taller than him in a position below his chest height.”

The Swans also said it was a “courageous submission” that Heeney would’ve been able to see Webster in the “0.01 seconds” he had.

“If his attempt was to hit, he wouldn’t have stopped … it’s completely inconsistent with the intention of trying to intentionally strike,” Miller said, describing the act itself as “bog standard”.

Tribunal chair Gleeson questioned the Swans’ point around the word “usually” in the new rule and the Swans described the rule as “beguilingly circular”.

The Swans argued there were exceptional and compelling circumstances, aka the “good bloke” rule, saying Heeney’s 193 games with two fines were at least close to the “gold standard” of Charlie Cameron escaping a ban for his 207 games of a good record (though he had been fined five times).

The AFL argued the rule did not apply, firstly because the Swans had not raised it before the hearing, but also because Tom Barrass failed with that ruling having played some 70 fewer games, and because Cameron’s case was unusual for several other reasons.

Meanwhile Adelaide failed to downgrade emerging superstar Izak Rankine’s four-game bump ban at the Tribunal.

Rankine’s hit which concussed Brisbane backman Brandon Starcevich was graded as intentional with severe impact and high contact, resulting in a whopping four-match suspension.

Even though Rankine sought out Starcevich off the ball, the Crows argued his actions were careless — not intentional.

“While Izak had no intention of making head high contact that resulted in the injury, it obviously did occur and that is not being contested,” Crows head of football Adam Kelly said.

“We believe however that a careless grading is more befitting of the incident.”

Andrew Culshaw for the Crows argued Rankine intended to bump the front of Starcevich’s chest, saying at home he thought Starcevich was winded initially.

But the AFL argued this was not relevant, just whether he intended to bump – and that Rankine “risked the consequences by electing to bump”.

Tribunal chair Jeff Gleeson asked whether the same bump, but excluding the head clash and only to the body, would be considered reasonable and the Crows said that was what was up for debate.

“If this bump had gone as planned, it was the sort of bump – admittedly off the ball – that you might see hundreds of times each weekend,” Culshaw said.

The Crows argued it was “unremarkable and not unreasonnable” to bump Starcevich in that situation given the defensive role he was playing on Rankine.

“The only bit that made it rough conduct was the clash of heads. And that bit was careless, not intentional,” Culshaw said.

However the Tribunal quickly return and found against the Crows, with Rankine’s four-game ban upheld.

Any concerns for Izak Rankine after this bump which floored Brandon Starcevich?

📺 Watch #AFLLionsCrows LIVE on ch. 504 or stream on Kayo: https://t.co/C09CBVNLUI

✍️ BLOG https://t.co/uBSfkgmUfD

🔢 MATCH CENTRE https://t.co/N0zk5aB9NX pic.twitter.com/DP473HXVmK— Fox Footy (@FOXFOOTY) July 7, 2024

HEENEY DECISION REASONS

The swing of Heeney’s arm was forceful, and it was more than a swatting motion. Having looked carefully at the vision, we find that it falls comfortably within the language of clause 4.3(b), the guidelines, in that he was intending to forcefully push or fend off Webster to gain separation for the purpose of contesting the ball.

The guidelines distinguish between push and fend in a way that makes clear that a fend means something different to or at least more than a push, bearing in mind the obvious purpose of the rule to reduce the incidence of blows such as this would be illogical to capture pushes, but not capture forceful swings of the arm.

Clause 4.3(b) states that if the effect of such an action is that the reportable offense of striking is committed, the strike will usually be graded as intentional. We find that this was the effect. It was a forceful blow to Webster’s face.

This part of clause 4.3 is only engaged if a player is not intending to strike, only intending to push or fend.

As a player whose conduct is captured by this provision will always be in a position of saying they did not actually intend to strike their opponent.

The provision makes clear it will usually be so graded. We do not find that there is anything about the circumstances of this offence that would reasonably characterize it as other than usual, given the natural language of the provision and the evident purpose of the provision.

As we have said, Heeney’s swing of the arm was a forceful blow, and he intended that blow to make contact with Webster, albeit not to his face. We are not satisfied that he intended only to make contact with Webster’s hands.

Then a submission that the act attracts the operation of regulation 19.6(a) two, in that there are exceptional and compelling circumstances which would make it inappropriate to apply the consequences of appendix one to the classification that’s been determined by the tribunal for an offence.

We do not find that the circumstances of this strike that has been graded as intentional render it appropriate to apply the appendix A classification.

Mr Heeney has a good record, and his immediate and genuine concern for the consequence of his strike were apparent.

This was an intentional strike resulting in injury, and accordingly, we consider a one-match sanction is appropriate.

RANKINE DECISION REASONS

Rankine forcefully bumped Brandon Starcevich a considerable distance from where the ball was trapped in a stoppage.

Both players were running in the same direction, and Starcevich was not expecting forceful contact. He had no reason to expect that he would be bumped.

The issue is whether Rankine intended to commit the reportable offence of rough conduct. In our opinion, it is clear that Rankine intended to engage in conduct which was unreasonable in the circumstances.

It was not reasonable to stop and forcefully bump Starcevich when Rankine must have known Starcevich was not expecting to be bumped.

Play had stopped, and although the bump was almost simultaneous with the umpire’s whistle, the Crows fairly accepted that neither player could reasonably have expected that the ball was about to come their way.

Rankine moved low and bumped in an upward motion. Starcevich was running at the time, he didn’t expect the bump and did not have the opportunity to protect himself.

Rankine must have known all of these matters, and it follows He intended to engage in conduct that was unreasonable in the circumstances. We were satisfied that this was intentional, rough conduct.

News

Thousands Stunned by Trump’s Strong 3-Word Warning to Police Association President Live at Arizona Rally

Trump’s three-word warning to police association president as he hogged the microphone at explosive Arizona rally https://videos.dailymail.co.uk/video/mol/2024/08/24/6616534242617541835/640x360_MP4_6616534242617541835.mp4 Donald Trump booted the president of the Arizona Police Association off the stage at his rally – telling him ‘you gotta go.’ Justin Harris joined the…

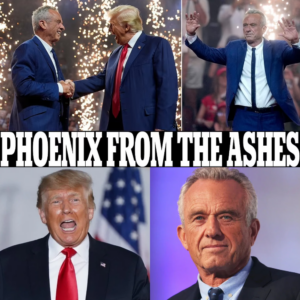

BREAKING NEWS Trump watches on as RFK Jr gives bombshell endorsement in Arizona – before former president issues surprise pledge

Robert Kennedy Jr. cemented his full devotion to Donald Trump before a raucous crowd of adoring supporters in Arizona Friday evening, finalizing his defection from the Democratic party. The nephew of Democratic President John F. Kennedy joined the former president on stage to a barrage…

Kamala Harris is finally cornered by a Fox News reporter after refusing to do an interview for more than a MONTH after Biden dropped out, once again confirming what we were already suspecting

Vice President Kamala Harris laughed off Fox News reporter Peter Doocy when he asked for an interview late Thursday night after her Democrat National Convention speech. ‘Hi Peter. How are you?’ Harris replied after Doocy called her name. ‘Congratulations,’ Doocy said before asking, ‘Are you ready…

Is this the real reason Beyoncé bailed on the DNC? KENNEDY’s savage takedown of Kamala’s night to forget

Maybe Beyoncé bailed on the DNC because she doesn’t buy this cheap Hollywood rebrand from ‘Kamala the bully’: KENNEDY’s savage takedown of Harris’s night to forget Where the heck was Beyoncé?! We were promised a diva but had to settle…

Kamala Harris unexpectedly send important message to Trump, causing his allies to ‘out of their minds’ as she makes important promises to all Americans

Kamala Harris launches blistering attacks on Trump and says his allies are ‘out of their minds’ as she makes major promises to all Americans Kamala Harris vowed to be a president who ‘unites us,’ pitching herself as a leader for all…

Kamala’s model stepdaugher Ella Emhoff sets internet alight with stylish DNC arrival, but what she said is what people care about most.

Ella Emhoff sets the internet alight with her appearance as she urges America to vote for her ‘Momala’ Kamala Harris Kamala Harris’ stepdaughter Ella Emhoff took the stage Thursday night at the Democratic National Convention ahead of her stepmom or ‘Momala’…

End of content

No more pages to load